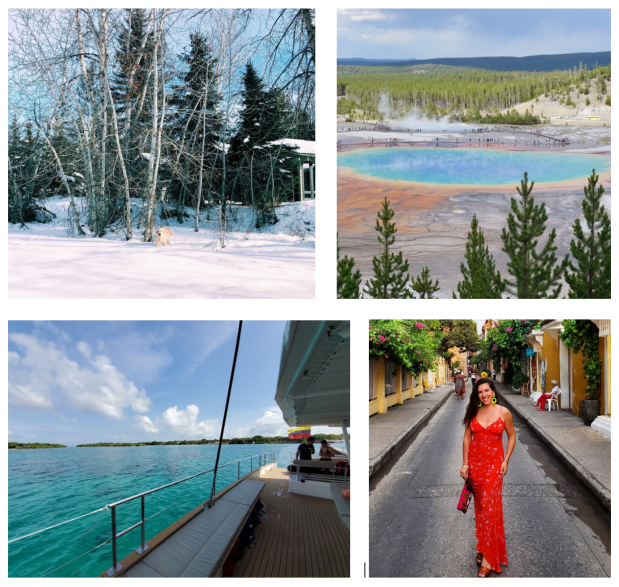

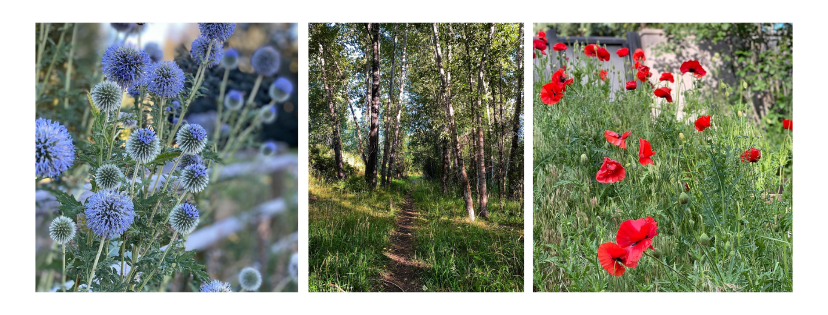

It’s cold enough this week in Idaho that my tears freeze on my eyelashes when I’m outside. Tiny little crystals gather, cool and sparkling, at the edges of my vision. They melt within seconds of coming back inside from my evening walks: a mile to River Run and a bit beyond, to the open field used in summer as grazing pasture for the Sun Valley draft horses. The waxing moon rises high above it now; the horses are nowhere to be seen. I’ve been walking this same route for seven months of solo strolls in the gathering dusk this year, often on the phone with a friend. I’ve watched the poppies—searingly bright—bloom and fade, the fuzzy thistles grow tall and wither. I’ve watched the aspen leaves swell, glossy and green, and then crisp underfoot, hidden now by soft pillows of snow. I’ve watched the river flow and freeze into a sheet of blurry ice.

Seasons change. So, as it turns out, do we. When I came to Ketchum last March, I expected to stay for a few weeks, maybe a month. I stayed for six. I was in London just a few days before, celebrating my friend’s 30th birthday in the neon-lit basement room of a karaoke club. We drank champagne and belted out ABBA tunes and glittered with hope and a little fear, a kind of festive desperation fueled by the looming crisis. I am grateful, now, for that last moment of joy. This year has been about living in memories, not making them. I would sit in the hammock on the porch this summer, reading Dune or re-reading Harry Potter, and a glimpse of something long forgotten would come lurching back: a raucous dinner at college, a heady evening in Spain, an afternoon spent in my childhood garden and its pungent scent of dirt and rhubarb and unripe strawberries. Faces, names, places. I spent a lot of time aching with remembrance: for people, some long gone. For youth, quietly slipping by. For feelings, of invincibility and hope, fading away. As the months wore on, something in me settled, though. The world seethed around me, around us, tearing sharp bits into our visions of community and healing. I helped craft obituaries, published pieces on protest and medical treatment, interviewed dozens of people dealing with the fallout of lives deferred. And isolated in Idaho, I sat, and I wrote.

I wrote about the deer I saw outside my window. I wrote about loneliness. I wrote about birds, and flowers, and the color of the grass when the sun hits it in the early morning, and the way someone’s unexpected text could make me feel. I wrote about being lucky, and being sad. There’s no bigger lesson in any of it, nothing I can say here or anywhere that means something great. At the end of each year, I used to try to pull out a grand moral in these blog posts, to share a story to illustrate something true. (Blogging? In 2020? What a concept, I know.) I have no truths that are worthy of much attention this time. I am just one 29-year-old woman, lucky beyond measure, sitting at a table in the corner of a house in a small town in Idaho, dreaming of something else and enjoying the golden feeling of afternoon sun on her left shoulder.

In the book Circe by Madeline Miller, the titular demi-goddess of Greek mythology is exiled to a lush but lonely island. (That list bit was relatable, for me.) “But in a solitary life, there are rare moments when another soul dips near yours, as stars once a year brush the earth,” Miller writes. “Such a constellation was he to me.” Circe is reconciling herself to the fate of a short-lived relationship, but I sense something bigger and more universal in the sentiment. The many kinds of souls that dip near me—stars of my past, hung in the night sky of my memory—wheel now near, now far from my thoughts. I am happy to have each of them, each of you, in my story, and I never want to lose a single one. In fact, I want more.

Happy New Year.

Things I did in 2020: Read the complete works of Jane Austen, and about 40 other books. Watched every James Bond movie. Ran over 200 miles, a personal best. Moved out of an apartment (mostly) and in with my parents (for now). Published around 100 articles, including two cover features for TIME (Halsey and BTS) and profiles of James Taylor and Rick Steves and Anitta, personal favorites. Wrote a couple of essays I’m proud of: about dating, and about Austen. Interviewed Mark Ruffalo and Emilia Clarke and Ellie Goulding and Jill Scott and more. Published stories about transformative youth voting and early COVID testing and sickness on campus and the power of art and the slow death of nightlife. Drank a lot of wine, and then a lot of tea, at home with my parents. Ate a lot of pasta. Hiked. Attended a beautiful Zoom wedding and a Zoom memorial. Made plans that almost all went awry.

Things I’m working on for 2021: Getting vaccinated. Finishing the last few pages of War and Peace. Trying out my hand at crosswords. Cooking more, particularly with my mom. Dating, in person. Writing, writing, writing. Holding hands. Making new plans. Updating this website, which I haven’t really done since, oh, 2013?